Photographing Angels – Part II

Once the brisk dawn air, still damp from a sudden shower, touched Geneva's face, all tiredness evaporated and she reached for her Nikon Coolpix digital camera in her messenger bag and set out for the Reading Terminal Market where she was assured of finding tasty food, a diversity of people and objects to photograph, and more importantly, the favorite diversion spot she looked forward to each time she returned to Philadelphia, the placed that served as an anchor, as "home".

Reading Terminal was not officially open for business yet, but regulars knew the Arch street door was unlocked for deliveries and several of the food vendors would already have fresh coffee and tea and pastries on display. She sat down at a Formica-topped table at Nunzio's Nook, a 1950's retro diner that anchored the enclosed farmer's market western wall. It was the best place on the planet for fresh "never frozen" juicy hamburgers and thick, intensely chocolate milkshakes.

Rows and rows of family-run stalls stretched before her with farm produce, bakery goods, flowers, arts and crafts, specialty food vendors, Pennsylvania Dutch meats and poultry, and dairy and cheese markets that took up an entire city block. Chefs from the finest local restaurants were already scouring today's offering for the freshest meats and produce before the doors officially opened to the general public.

She settled down for a relaxing cup of chamomile tea and allowed her mind to wander, a delicious freedom she rarely had time to enjoy. Resting her chin in the cup of her palm, she closed her eyes and felt the bone-weary tiredness overtake her again. She felt herself falling without the energy to stop the descent and then was startled awake when a crate of oranges fell to the floor sending a gunshot sound through the aisles of stalls now bustling with customers.

***

Geneva stretched and raised her camera and focused the lens on a five star local celebrity chef from Le Beq Fin carefully smelling tomatoes and juggling lemons in the air. She panned the camera lens to follow the arc of the lemons and found herself staring into the lens of another camera apparently focusing on her. She lowered her camera and looked at the teenage boy in a wheelchair. He panned his camera left and right, stopped to smack the top of the camera with his right hand and then panned the camera again. Finally he dropped the camera in his lap and lowered his head. The man and woman on either side of the boy's wheelchair leaned into him. The woman stroked his hair while the man picked up the camera and fidgeted with the buttons. He noticed Geneva watching him, noticed her camera and immediately crossed the twenty steps separating them. The woman, pushing the wheelchair followed him.

"Excuse me, Ma'am. Darin plans to be a famous photographer someday but right now we are having trouble with his new digital camera. Do you know anything about digital cameras?"

"A little," she said, studying the vacant stare in the boy's eyes. "Good, we are in luck. He's using the same model camera as mine."

The boy looked up and stated, "Nikon Rocks!"

Geneva laughed and leaned into the man so that only he could hear her words. "Is your son blind?"

"Yes, as of six months ago." He looked into Geneva's eyes as so many other parents had when seeking understanding more than her help. "It must seem ridiculous to you…. A blind boy with a camera."

"Unusual, yes," Geneva replied.

We gave him a camera for his sixteenth birthday six months ago. He was fooling around with his friends and trying to take pictures of his friends doing motor-bike jumps over a stack of logs. Billy, his best friend, miscalculated his jump and plowed right into Darin. He fell back into the logs…."

"I'm sorry," Geneva said.

"It really threw Darin for a loop. He isn't snapping out of his depression and just seems shut down. I found this new camera with automatic focusing and metering. So he could still take pictures even though he couldn't see. It's the first thing to interest him since the accident. Now he seems obsessed with trying to capture a photograph of these strange lights that he sees.

"He was so active before," the boy's mother added.. Now all he can see is dim light and blurred shapes."

"And flashes of color now and then," the father added. "Though we don't know if he is really seeing color or just remembering it."

"Maybe the color is an artifact of brain function, not something actually visually perceived," Geneva said. "Neurochemical color."

The boys' parents stared at her. She could see their ease with her slipping away on the heels of her technical words.

"But then what do I know?" she said. "I read a lot and sometimes think I know more than other people. It's a bad habit." She studied the camera. "But I have good news about the camera. There's nothing wrong with it that a new lithium battery won't fix." She reached into her messenger bag and extracted a spare camera battery and installed into the boy's camera. "There, she said. It will work now." She scrolled though the digital photographs stored on the camera's memory card.

Geneva expected to see blurred images without form or artistic composition but was surprised to find subjects caught in sharp focus yet skewed in a fascinating manner from a different perspective that gave them new meaning. "Darin, these are very interesting," she said as she stepped over to the wheelchair and kneeled down beside him.

The boy smiled and raised his head. "You like them? Really?"

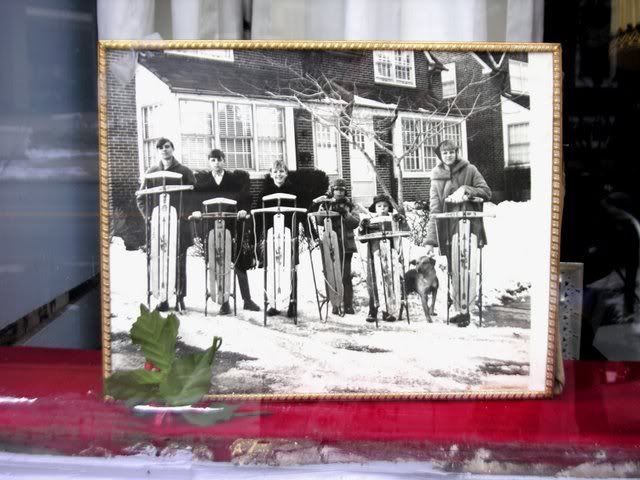

"Oh yes." She continued to scroll to the end of the images. "I especially like the ones of the beagle. Is that your dog?"

"Those I just took for fun. Did you see the one of him wearing the antlers at Christmas? Did I really get the antlers in the picture too? Mom and Dad says all my pictures are good but you know how parents are."

"Indeed I can see the antlers," Geneva said. "There almost as big as the dog."

She scanned through the photos for a second time and caught her breath at a picture of an older woman eating grapes from a nearby fruit stand. The photograph was of herself. But that was impossible! She had not yet ventured on her tour of the stalls that would take up the remainder of the morning and end with several bags of fruit, vegetables and cheeses to take home to her apartment.

"You even caught a photo of me," she said dismissing thoughts of the improbability, impossibility of the photo. She must have simply forgotten stopping by the fruit stall on the way into Reading Terminal. "I look older than I realized," she said. "And far pudgier than I want." The boy laughed.

"You do seem to be having some trouble with your ISO setting in some of the photographs. Some of them are a little blurred with flashes of light. Almost like a double exposure. I can reset the ISO value to a lower number. That might take care of it."

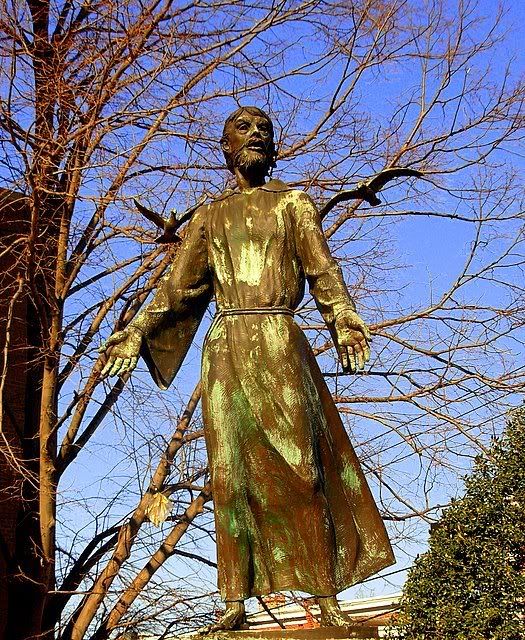

He smiled and took the camera from her, fingered it until he found what he was looking for and then pushed the shutter release button. This time it snapped as it should. "Blurring?" he said as his eyebrows arched in thought. "Oh, you mean the angels?"

"Angels?" Geneva asked with her eyebrows arched to match his.

"At first, I thought it was just strange lights that I was seeing. Especially right after the accident. But then I figured it out. It's angels. They are like hummingbirds. Hard to photograph no matter what film speed you use."

***

Long after the boy and his parents left, Geneva pondered the thought of photographing angels. It was remarkable how people coped with crushing adversity. Who was she to try and dissuade a young boy from his thoughts and images of angels. To a cold impartial scientific mind, his "angels" were nothing more than symptoms of detached retinas. But as she finally opened and read the results of her MRI scan and other test results sent by her doctor, Geneva wondered if their couldn't be room for other ways of diagnosing reality.

"Bad news?" a voice said from behind her.

She turned to face a tall, lanky middle-aged man dressed in jeans, black turtleneck sweater and wearing sandals. Benjamin Bernard, a friendly, capable man who filled in for Penn's chaplain when the chaplain was away on vacation or attending meetings. She'd only met him a dozen times or so at the hospital but each time had been thoroughly positive with the way he ministered to families in time of crisis.

"Bernard," she said. "How nice to see you again."

"Likewise," he replied and motioned again to the file she was reading. "Bad news about a friend…someone you care about? It must be, from the expression on your face."

Geneva nodded. "Confirmed Alzheimer's," she said. "Progressing at an accelerated rate. Memory loss, intermittent amnesia. Neurological manifestations. All leading to total disability in the near future."

"There aren't any treatment options?" Bernard asked.

"Oh sure," she said. "Some aspects of the disease can be mediated but the progressive cognitive loss can't be stopped." She closed the folder. "In six months this person will not remember their name on infrequent bad days. And on good days, they won't be able to work or balance a check book, or follow the plot of a movie. And worst of all, they will know that things are only going to get worse."

"I'm sorry," Bernard said. Dementia is the hardest thing to counsel a family about."

"There is no family in this case," Geneva said.

Bernard shook his head.

"But please, Bernard, let's think of happier things. Tell me of your newest plot to convert the citizens of Philadelphia."

Bernard winced. "When I turned forty, I realized how smug I used to be, how I force fed the Gospel to anyone I could button-hole. Though I thought otherwise at the time, there wasn't much difference between me and the dogmatic teachers of the tradition that I abandoned. I just packaged the message differently, adorned it with New Age garlands, though at the heart of it, it was still involved in forcing others to agree with me."

"Bernard, I'm sorry. I wasn't implying that you aren't genuine, In fact, you are one of the most genuine people I know."

"Thanks," Bernard said. "I didn't take offense."

"So tell me what's happening at the mission you opened last year. It's just down Arch Street, isn't it? The storefront next to the Chinese take-out restaurant?"

"Yes, I'm still there. I thought it was going to be a matter of ministering mostly to the homeless. A soup kitchen, AA meetings, a stopping place for the mobile health clinic, that kind of thing. But it's turned into something quite different."

"Really?"

"Yes, I seem to be dealing more with those who are just a paycheck or two away from homelessness. Those who are just barely holding on. Where even the slightest adversity will push them over the edge. A lot of seniors. A lot of single mothers. And quite a few from nearby businesses who stop by on their way home from work."

"What is it that you actually do there? Hold church services and bible study?"

"Well, there is a chapel and I do have a regular service twice a week, but mostly I just prop the door open in the morning and see what happens."

"Well?"

Well what?"

"What happens?"

"Okay, take yesterday for instance. Juanita Garcia stopped by on her way to work with her three-month old baby. She chatted for a moment, changed the baby's diaper and left."

"And?" Geneva prompted.

"She works across the street as a seamstress for the laundry and drops her baby at the subsidized Episcopal Church daycare down the street. At noon, she stopped by with her baby again for her thirty-minute lunch break, fed and changed the baby's diaper and returned the baby to the daycare center and then went back to work." Bernard paused again, obviously enjoying Geneva's frustration at him for not getting to the point.

Geneva drummed her fingers on the table.

"And then, since Juanita works twelve hour days at the laundry, her husband Jose, who can only find day work now and then, picks up the baby from daycare and then he stops by to give the baby its bottle and change the diaper again. He talks about his family back in Mexico, how he misses them. And then he takes the baby home,"

"And the point to this story is what?" Geneva asked.

"It took me a couple of weeks to figure it out. I keep disposable diapers in the bathroom for emergencies when parents forget to bring them. Do you know how much disposable diapers cost?"

Geneva shook her head.

"Well it's more than Juanita and Jose have to spend. How are they supposed to make the choice between buying baby formula or disposable diapers? The choice between buying a bag of rice for their dinner or buying disposable diapers." He shook his head. "I never realized the choices some people are forced to make, day in, day out, the kind of choices that wear down your humanity and self-respect, inch by inch. So now I stock disposable diapers in every size in the bathroom. I keep formula powder in the kitchen along with bags of nuts and fresh fruit and nutritional snacks. And then people don't have to make those choices. At least for today. And sometimes they sit down and talk about their day, about their lives while eating a handful of nuts or munching on an apple and they don't feel ashamed or worn down anymore. It's about offering only what is needed, not as a handout but just as something a friend might have on hand when you drop by for a visit. That and nothing more.

"A mission in the wilderness, indeed," Geneva said.

Bernard pulled a folded flyer from his pocket. "And on the lighter side, we have this for another population, the employees of nearby businesses who have plenty of disposable income but who seem to be empty otherwise. And searching. I started a series of workshops on subjects of general interest. The Arts Council thankfully has picked up the tab for supplies." He unfolded the flyer and slid it across the table to Geneva. "We've done Zen meditation, watercolor classes, even had a local astrologer come in and give readings. It has drawn together such an interesting community of neighborhood residents, day workers, and now there is always one or two of them hanging out to chat together at any time of the day or night."

Geneva unfolded the fluorescent fuchsia flyer and smiled at the contents.

"Remote Viewing for Dummies" Workshop

October 8, 2008

Sponsored by

The Philadelphia Arts

Council Neighborhood

Enrichment Series

Location: Wilderness Within Mission

Arch Street & Linden Avenue

Tuition fee: Free to neighborhood residents

All others - $5

Instructor: Brother Benjamin Bernard;

Founder, Wilderness Within Mission

The textbook, "Remote Viewing for Dummies," and the blank journal provided by the Philadelphia Arts Council are an invitation to suspend your disbelief, uncover your hidden creativity, share an evening with friends, and exercise your sense of adventure as well as your sense of humor.

The instructions are simple. After our centering and relaxation exercises we will concentrate on a specific geographic location identified only by its' GPS location. As a group, in stillness and quietude, we will hold this location in our imagination. In your journal, make notes of any images, feelings, or thoughts that come to mind. There are no right or wrong answers or time limits. Over the next few days or weeks, you may want to add additional notes or images for a particular location. During the next twelve weeks of this series, we will visit some of these locations in person or through photographs and compare what is there with what we recorded in our journals.

"What fun!" Geneva said. "Even if Remote Viewing is a crock. Say, you didn't happen to have a workshop on photographing angels, did you?"

"Pardon?"

"Just a joke," Geneva said. She raised her camera and focused on Bernard's amber-green eyes. She wondered if she could capture the required number of pixels to convey his compassion and the willingness of his open heart to make room for everyone. "Clearly an angel unaware," she said as she snapped the photo.

"Say, you wouldn't be interested in leading a photography workshop at the mission, would you?" He immediately shook his head. "But I suppose you are too busy…."

"No," Geneva replied. "I didn't realize it at the time. But something has come up." She slid the letter from her doctor across the table to Bernard. "I wandered away from myself today. Right here in Reading Terminal. And I didn't even realize it until a blind boy saw me and pointed it out."

As serene as Bernard projected himself in other troubling circumstances, this time he could not cover his confusion and anxiety. "Dear God in Heaven," he said looking down at the letter. "You are the Alzheimer's patient."